Our indigenous people are waging wars on numerous fronts. It’s bad enough that many of the Lumads of Mindanao are fighting for the right to live, but some are also fighting an enemy that is both faceless and relentless: climate change.

Take the Lumads of San Francisco, Agusan del Sur, for example.

Dry spells in the region can last up to months, affecting thousands of hectares of farm land. With no proper irrigation, rice and corn wilt and agricultural production loss worsens. On a national level, over a hundred thousand hectares of land were affected from September 2014 to August 2015 by prolonged dry spells resulting to a production loss of 281,860 million tons, according to the Department of Agriculture (DA). “Hindi lang mais at palay, pati mga gulay naming naaapektuhan din. (Corn and rice are not the only crops affected, even our vegetables are affected,” farmer William Abatayo said.

Coco Nets to Stop Soil Erosion

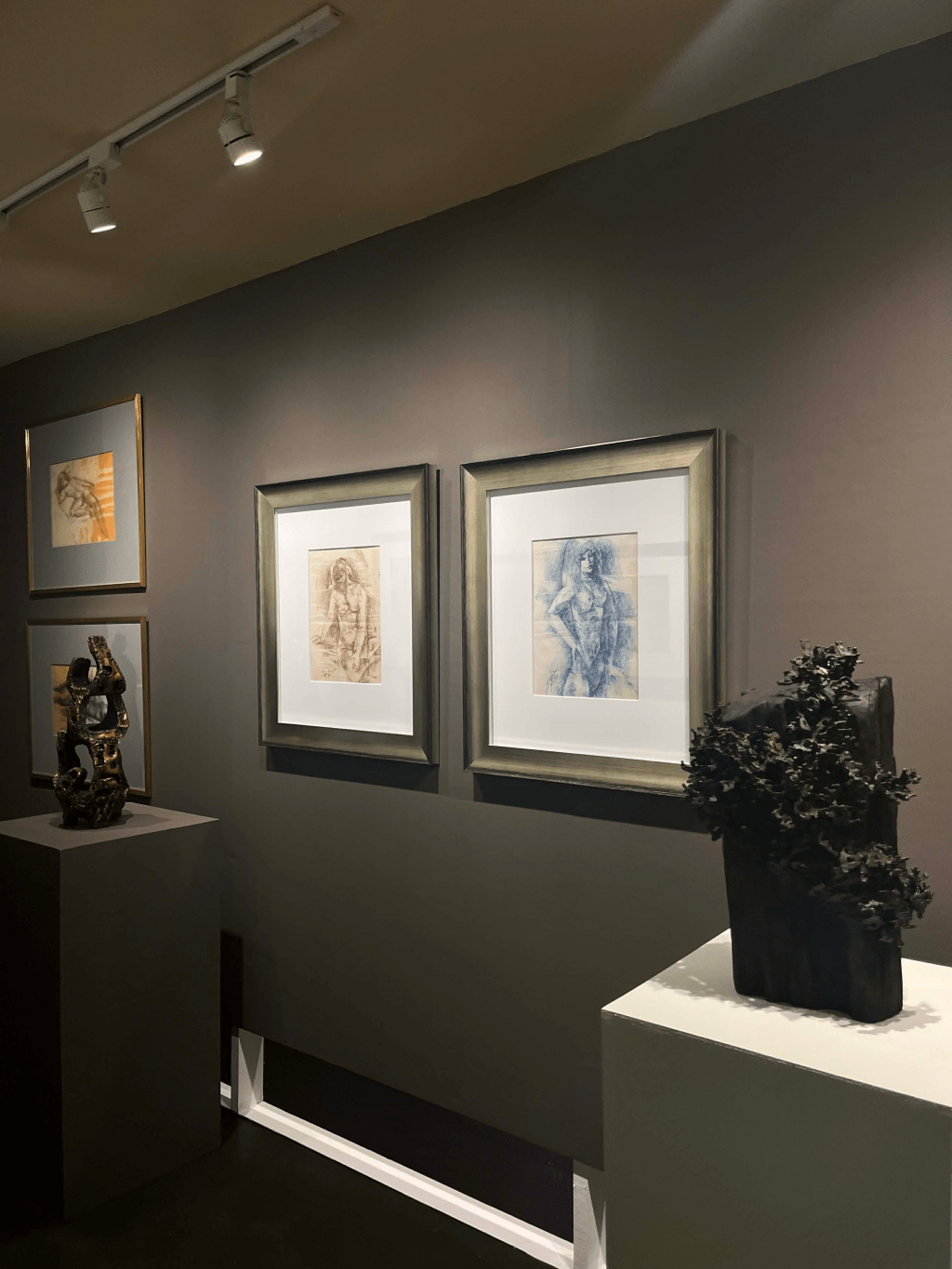

With major crops floundering, the Lumads turn to alternative livelihoods such as coco coir weaving for additional income. Dried coco husks are processed in a grinding machine until the fibers are extracted. Once the fibers have been collected, locals will then weave and twine these fibers into rope-like materials used for coco nets.

Margie Espina, 42, has been weaving for three years, earning P600 a day from producing two rolls of coco coir from almost eight hours of twining. On weekends, children help their parents at the community working station.

The Caraga Administrative Region where the small town of “San Franz” is located currently produces the largest volume of coco net in the country, according to the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA). Coco coir has a proven high-tensile strength which makes it a valuable material for vegetation and land rehabilitation. The material promotes vegetation by keeping the soil nutrients intact. “Each coco coir plant generates up to 1,200 jobs. Coco nets are used to prevent soil erosion in critical slopes, embankments and roadsides,” PCA Project Development Officer Grace Orilla said.

Saving the Soil

According to the PCA, 54 mining companies have been operating in the region, with a minimum of 5,000 hectares due for rehabilitation. But land rehabilitation could not be done overnight. In fact, according to the DA-Caraga, it takes roughly 125 years to fully restore degraded soil caused by mining. “Continuous mining contributes to land degradation and erosion. If left unchecked, chemicals can flow to rivers and seas and can affect the habitat of the fish,” Dir. Edna Mabeza of DA-Caraga said.

United Nations Drylands Ambassador Dennis Garrity offers a simpler solution: replace mined-out soil with top soil for vegetation.

“If you protect the land it will naturally regenerate very rapidly. In other countries like United States, coal-mined areas regenerate very rapidly because mining companies are required to put soil back and plant trees so they can restore the land,” Garrity said.

Money in Mining

Despite the environmental effects of mining, the industry flourishes in the country. The Philippines ranks as the 5th most mineral-rich country in the world. Thirty one percent of mining contracts in the Philippines are issued in Mindanao in 2013, according to the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB).

Mining has also proven to be a lucrative business, with P204.7 billion worth of production value in 2014, according to the MGB. This year alone, the MGB has reported a 32 % increase in royalties collected from mine operation. (P763.66 million in royalties from January to June, up from P577.55 million in the first half of 2014).

Under Section 5 of the Philippine Mining Act of 1995, “ten percent share of all royalties and revenues to be derived by the government from the development and utilization of the mineral resources within mineral reservations… shall accrue to the MGB.” This share shall be “allotted for special projects and other administrative expenses related to the exploration and development of other mineral reservations.”

Meanwhile, indigenous people who live in ancestral lands explored for mining only get one percent of the gross revenue of the sale of minerals, as required by the Indigenous People’s Rights Act and the Philippine Mining Act.

This share is managed by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, along with the tribal community managing or living in the ancestral land used for exploration.

Life Tied to the Land

For the Lumads, land is their life. It is their home and their source of living. Without healthy soil and rain to water the parched lands, agricultural sustainability will not be feasible. Lumads might be threatened by longer dry spells, soil erosion, and land degradation, but they learn to adapt.

Coco nets can keep the soil from falling apart for now, but for how long, only time can tell.

[Entry 108, The SubSelfie Blog]

Editor’s Note: This was first published on GMA News Online. Photos: Hon Sophia Balod /DA-CARAGA

About the Author:

Hon Sophia Balod is the Global Editor of SubSelfie.com. She is also Editor in Chief and Outreach Manager for the Seafood Trade Intelligence Portal and foreign correspondent for GMA News. She graduated from the Mundus Journalism Masters Programme in University of Amsterdam in 2018.

She is the recipient of the 2019 Outstanding Media Award given by the Media Correspondent and Volunteer Organization (MCVO) in The Hague, The Netherlands. She is a media fellow of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and recipient of 2016 Gawad Agong and Sarihay Media Awards for Excellence in News Reporting on the plight of indigenous people and environmental issues. Journalism 2010, UP Diliman. Read more of her articles here.

Leave a comment