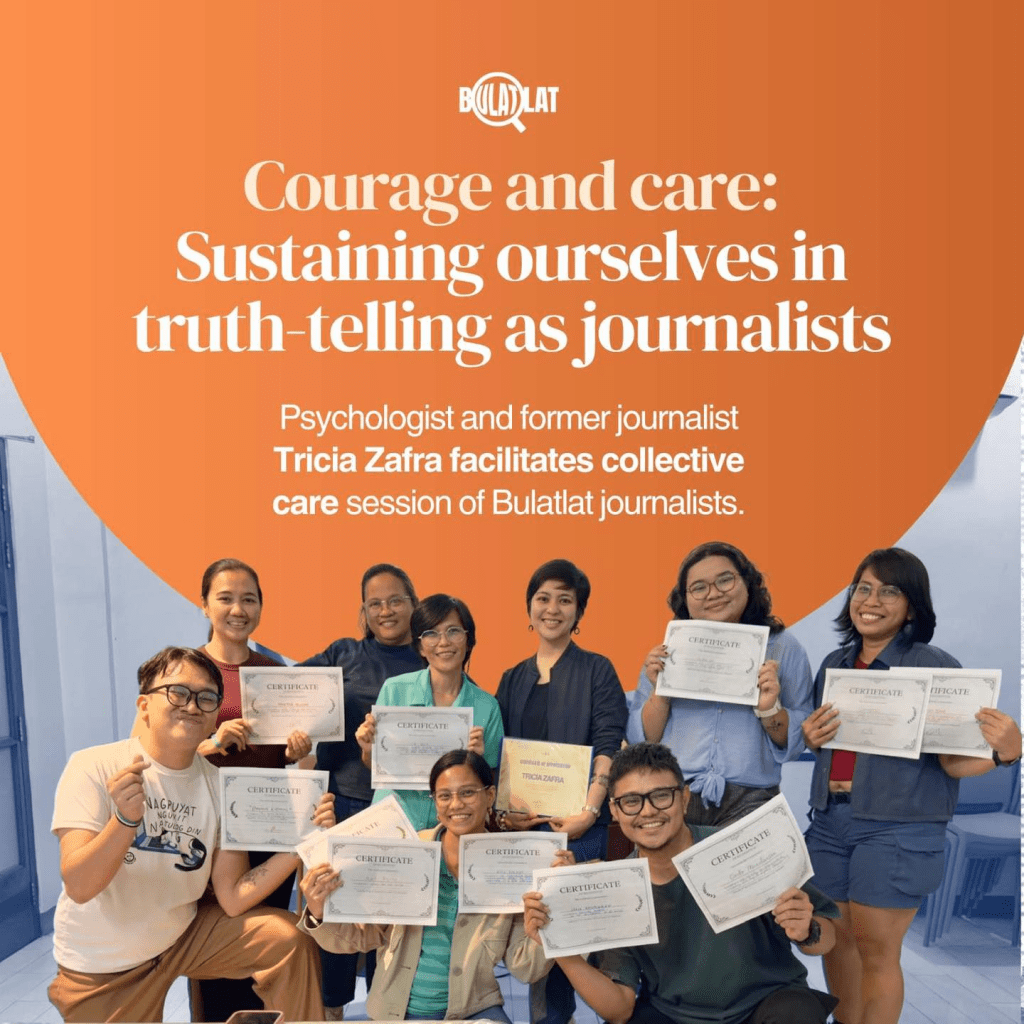

When Bulatlat’s Editor-in-Chief Len Olea reached out to collaborate on a mental health session for their staff, I was in awe. In the news industry that I knew, it’s rare for news managers to keep an eye on psychosocial well-being of the staff. And maybe that’s why earlier this year, during International Women’s Day in March, the Asian Center for Journalism at the Ateneo de Manila University, gathered female industry veterans and news managers for the National Conference of the Movement for the Safety and Welfare of Women Journalists (We-Move). One of the sessions was devoted to mental health. Olea attended this, and she has become more determined to ensure a newsroom where journalists feel safe and supported. In our alignment meeting before the session set for the Mental Health Month in October, Olea emphasized that their goal is to continuously strengthen their culture of collective care. This personally elicited in me a sense of hope. The professional culture I once knew is now shifting.

Photo credit: Bulatlat

As a former journalist, the job could be pretty isolating despite the shared experiences of distress and trauma. It’s just something that’s not talked about (except when it becomes a news story itself). The norm was to shrug it off or shove it down. That’s how resilience was framed. Finally, that’s now changing.

This year’s Mental Health in Journalism Summit held online globally from October 8 to 10, by nonprofit The Self-Investigation and Fred Foundation, had the theme: “Resilience for uncertain times.” The summit is reframing resilience to include open discussions and exploring solutions to address mental health issues among journalists. They believe that mental health is necessary to sustain good quality journalism. Executive director and co-founder Mar Cabra also emphasized the importance of engaging newsroom managers in rebuilding a healthier media workplace culture: “If there is one place to truly start and where the greatest organizational impact can be achieved, according to the WHO, it is by training editors and people in senior management positions.”

I joined the more than 160 speakers of the summit from over 40 countries and presented two sessions. I conducted an online workshop to help journalists check their stress using self-assessment tools and encourage them to act adaptively to it. I was surprised to see journalists and editors from different parts of the world actively participate in the workshop. I didn’t expect the level of interest in practical coping strategies.

On the third day of the summit, I gave a five-minute lightning talk to explore the idea of making self-care an ethical responsibility in journalism. Various media organizations have already developed guidelines supporting the mental well-being of journalists. Yet, when we look at the individual experiences of journalists, there still remains a huge gap between what’s written on paper and how these individuals are able to care for themselves given prevailing organizational cultures. I believe that by including self-care in the journalism code of ethics, self-care won’t be framed as an individual responsibility anymore, but a collective one. This will then speed up the change in professional culture.

On the morning of February 2, 2007, photojournalist Charlie Saceda spent over 30 minutes staring at the aftermath of a chemical explosion in Tigbao, Zamboanga del Sur where 50 people were killed and dozens were injured. He was not in shock or lost in thought. He was figuring out how to take photos of the gruesome sight. He was thinking of the audience.

Saceda shared this during the media safety session of the mental health support intervention conducted for Cebu-based journalists who survived and reported on the September 30 earthquake. He points out that a journalist who is prepared and whose stress is managed will have more headspace to care for their bottom line: the audience. I agree. This is where ethics come into play when we talk about self-care in journalism.

The mental health session conducted for Cebu-based journalists was in response to the call for support from journalists themselves, facilitated by the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) – Cebu. It feels surreal. I remember a time when talking about distress after surviving and covering disasters and emergencies was taboo. At the same time, it’s inspiring. The call was made by the younger generation of journalists. They are driving the cultural change in newsrooms. To me, that’s courage: speaking up about what you need and asking for help. Because journalists are humans, too.

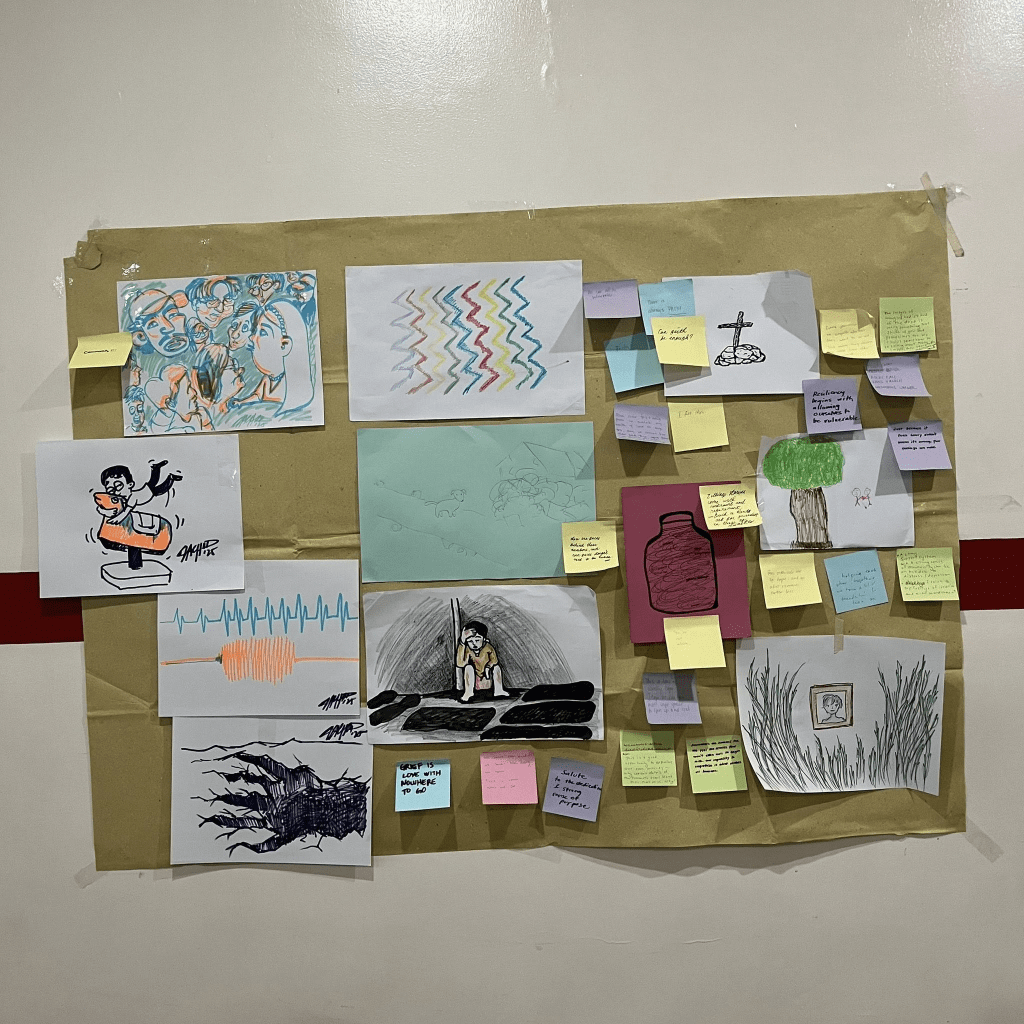

Photo credit: NUJP Cebu

By the end of the two-day session facilitated by the peer support programs of the Peace and Conflict Journalism Network Philippines, Inc. (PECOJON), and the NUJP with the support of the Movement for Media Safety Philippines (MMSP) and donations from fellow journalists, the participants came up with their collective mantra, “embracing ourselves in recovery. ”

It’s a mantra that we hope will serve as a reminder that they need to care for themselves and each other to keep seeking and telling the truth, and that they have the power to drive the change that’s needed towards humane, sustainable, and ethical practice of the profession.

***

Leave a comment