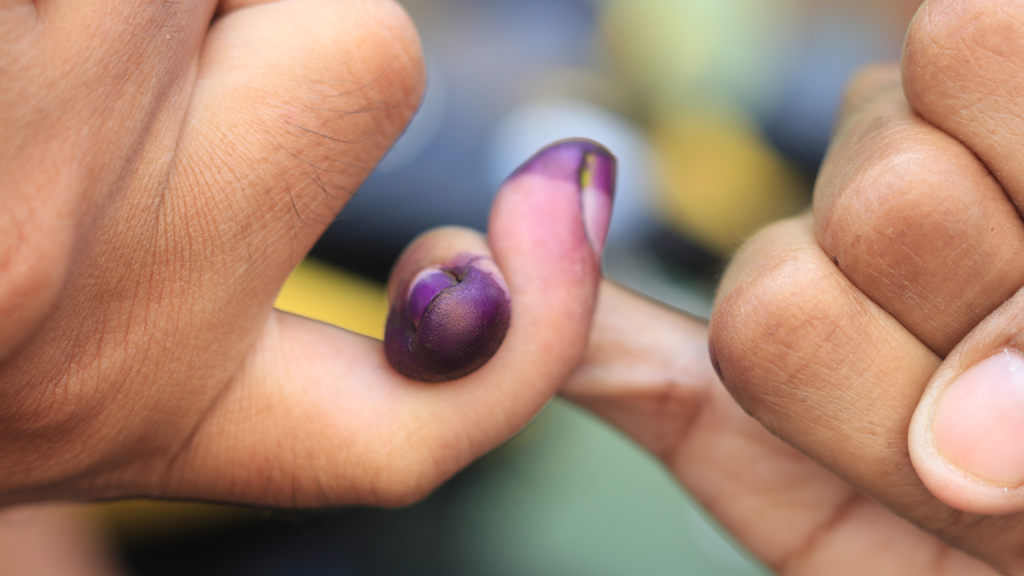

Results from the recently conducted 2025 National and Local Elections (NLEs) served as a grim reminder of the country’s tendency to vote for the worst of the worst.

However, recent developments show that this might not be the case, and that Filipino voters are damned to a very conscious and very material system that actively subjects citizens to a historically repetitive process of democracy being thrown right back at their faces.

Somehow, this year’s election results also show the possibility of today’s voters becoming more conscious by the minute, more conscious of their bastardized state, even just by a little bit.

The country’s history with electoral sabotage remains lively to this day. In order to provide a safer, more efficient means of voting, Vote Counting Machines (VCMs) And Automated Counting Machines (ACMs) have been introduced to the Philippines as early as 2007 via Republic Act No. 9369 otherwise known as the Automated Election System (AES) Law, solidified during 2010, and implemented full-scale during the 2016, 2022 presidential elections, and the NEL 2025. Consequently, the use of ACMs/VCMs for NLEs caused newer conflicts mostly rooted in human malice and insidious agendas – not by the machines’ malfunction.

Back in 2023, the National Press Club of the Philippines (NPC), Automated Election System Watch, and Guardians Brotherhood Inc. filed a complaint against the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) due to alleged electoral sabotage and other electoral mishaps ranging from the printing of ballots without the presence of officially recognized poll watchers to a possible configuration issue with the VCM’s SD cards. Similar issues also surfaced on the contractor’s end, with Smartmatic VCMs being subjected to public scrutiny due to the lack of traceability of the company owner, as well as MIRU Systems – the most recent and lone bidder and current supplier for the ACMs used in this year’s NEL – and its vulnerability to hackers, causing numerous cases of vote recounts throughout other contracted countries especially Iraq.

These issues involving the security of the ballot became the primary point of concern for most countries, which is why almost 142 countries have yet to subscribe to ACMs to modernize their electoral procedures. Interestingly enough, the Philippines is among the 35 countries that have already integrated electronic voting technologies despite unresolved logistical issues.

In 2024, former Caloocan Congress Representative Edgar Erice aired his concerns on the acquisition of MIRU Systems as the sole bidder and now-awardee of the Full Automation System with Transparency Audit/Count (FASTrAC) contract issued by COMELEC.. Erice posits that although it is being advertised as a relatively cheaper supplier compared to its predecessor Smartmatic, the project costs PHP 17.99 billion – the biggest election-related expense throughout Philippine history – further mentioning that the endeavor is at risk of incurring PHP 10 billion in losses.

Somehow, this proves to be true.

On election day, numerous reports of election-related violations, discrepancies, and other saboteurs to the electoral process have taken social media by storm. The Computer Professionals Union (CPU) criticized COMELEC in a statement, saying that COMELEC blatantly abuses the parameters set by the AES Law by enacting unofficial changes and tweaks to the ACM’s operability. They cite cases involving unauthorized software updates bereft of any presence from pollwatchers and media personnel, non-issuance of Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trails (VVPATs) to Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), and ACM errors that put the integrity of every ACM-processed vote into question. To retort, COMELEC, through Pro V&V – a third-party International Certification Entity – mentions that the only changes implemented were limited to the File Name, Version Number, and Hash Values. Under the AES Law Section 9, COMELEC is allowed to make use of third-party service providers as part of the advisory council, given that these institutions would be subject to the same prohibitions and penalties.

It is interesting to note that Pro V&V’s Final Source Code Review Report dated April 30, 2025 was said to be outdated, given that it was utilizing the findings from March 28, 2025 – a version without the updated findings of MIRU Systems. The independent certification entity also mentioned that they updated the report and released the latest version as early as March 29, 2025, 9:00 AM Manila Standard Time at Huntsville, Alabama.

Aligned with this, AES law Section 11 mandates the conduct of a Mock Election as part of the Technical Evaluation Committee’s confirmation that both the software and hardware of the implemented AES are operating “properly, securely, and accurately.” It also requires a timeline not later than three months before the electoral process. With this, COMELEC was able to hold Mock Elections last January 25, 2025.

Suffice it to say that the context of the January-dated Mock Elections made use of the previous ACM v. 3.4 version; this would imply that the March 29-dated ACM v. 3.5 will not guarantee to reproduce the same conditions and outcomes as the January-dated Mock Elections.

Regardless of the circumstances, the results cannot be denied: discrepancies in the voter turnout were reported by CPU in droves, given that the number of casted valid ballots is more than the actual voters who voted.

While COMELEC points the fault to the users, not recognizing the validity of the reported discrepancies, they fail to recognize the inaccessibility of the ACMs, especially towards the elderly and the physically disabled. Concerned netizen Joy Bernos posted a video on Facebook last May 12, showing poll watchers shading ballots from elderly folk under the guise of assisting them. Inquirer also reports on the hassle faced by many Senior Citizen voters in Cavite, mostly involving how they are being told by poll watchers and canvassers to come back due to some technical difficulties with the issuance of their VVPAT.

On a larger scale, Vote Report PH released a report last May 13 confirming 1,593 cases of various election-related violations, ranging from ACM errors to disenfranchisement or invalidation of ballots, covered across 229 cities and municipalities in the country. This begs the question of whether or not the country might have rushed too soon in adopting electronic voting systems. Although some perspectives might believe that the Philippines’ inclusion to the 35 countries that has adopted electronic voting systems is a sign that the country is at the forefront of development, one would also suggest that the Philippines might be forgetting something crucial that prevents it from being considered at par with the big countries that are part of the same roster.

The Philippines is poor and underdeveloped.

Given the country’s reputation for its citizens not faring well with global literacy comparisons, not to mention the lack of digital literacy amongst most citizens, the pursuit to adopt advanced technologies becomes immature and inappropriate to the Philippine situation and context.

In other words, Filipinos are made to simply idealize the elections, with little to no understanding of how material and how conscious these systems work to oppress and take advantage of their socio-economic and socio-political vulnerabilities.

But despite these odds, this year’s NLE proved to be significantly better.

Compared to the one-sided dominance of the 2022 elections, this year’s results provided promising developments. Although political criminals and butchers still managed to secure office, wrongfully vilified candidates still managed to obtain support from the people. The opposition continues to gather strength day by day, as the standard for Philippine politics continues to be changed and reshaped and redefined for the better.

Despite these odds, the country fared well, with much better circumstances.

But then again, traditional politicians, political dynasties, and criminal candidates would still be in the Philippine political scene. Still, some citizens will inevitably vote for them. But under no circumstances should the citizens be referred to as stupid; there is no benefit to the “bobo-tante” narrative. Either way, the situation will sort itself out because, ironically, these atrocious political figures will be the ones to hasten the process.

Thanks to the country’s problematic political figures, it only took three years for these distant and individual frustrations to become concerted and undeclared common understandings.

So yes, let them win; let them dominate and prevail. Let these atrocities become the accelerants for the collective decision to redefine Philippine politics.

The Filipino people can only bear so much.

About the Author

John Thimoty Romero is a Senior High School teacher at Mapúa University – Makati. Upon his graduation as Bachelor of Secondary Education – Major in English, he received the Gawad Graciano Lopez – Jaena award for his service as Editor-in-Chief of Philippine Normal University’s official student publication, The Torch Publications. He publishes his views and opinions through his blog, The Pinoy Meddler.

Leave a comment